The Mirror of Charity

Series: Monastic Studies Series 26

ISBN: 978-1-60724-200-0

Aelred of Rievaulx possessed a personal charm which drew friends and disciples naturally to him. His own experience of human weakness in a worldly life at the court of King David of Scotland made him sensitive to the doctrine of charity which he found among Cistercian monks. The Mirror of Charity gives us a solid theology of the Cistercian life. Because the divine nature is love, as the Bible tells us, directing our love to God-love conforms us to the image of God that has been lost through sin. All love, to Aelred, is a participation in God-love that leads us to union.

$187.00 (USD) $112.20 (USD)

Homilies in Praise of the Blessed Virgin Mary

By Bernard of Clairvaux; Translated by Marie-Bernard Saïd; Introduction by M. Chrysogonus Waddell OCSO

Series: Monastic Studies Series 23

ISBN: 978-1-60724-201-7

The young abbot meditates on the singular role of the Virgin Mother of Christ 'to satisfy [his] own devotion', and in doing so bequeathes his own love of Mary and of Scripture to his Order and to the Church.

$142.00 (USD) $85.20 (USD)

Eight Homilies on the Praises of Blessed Mary

Series: Monastic Studies Series 24

ISBN: 978-1-60724-202-4

Amadeus became a monk of Clairvaux in 1125, just about the time its abbot, Bernard, began to be noticed by the Church at large. After twenty years in the cloister, Amadeus became bishop of the troubled diocese of Lausanne. Reform and renewal did not come easily. Amid political skullduggery, as well as the demands of pastoral and administrative duties, Bishop Amadeus managed to write–perhaps to preach–these eight homilies in praise of Mary. Formed as a monk under the charismatic influence of Saint Bernard, Amadeus retained a distinctive piety which finds eloquent expression in this series of sermons, almost all that survives from his pen.

$116.00 (USD) $69.60 (USD)

In Praise of the New Knighthood

A Treatise on the Knights Templar and the Holy Places of Jerusalem

Series: Monastic Studies Series 25

ISBN: 978-1-60724-203-1

The monk and the knight—the two quintessentially medieval European heroes—were combined in the Knights Templar, men who took the monastic vows and defended the holy places and pilgrims. With characteristic eloquence, Bernard of Clairvaux voices the cleric's view of the knights, warfare, and the conquest of the Holy Land in five chapters on the knight's vocation. Then, in another eight chapters the abbot who never visited the Holy Land provides a spiritual tour of the pilgrimage sites guarded by this 'new kind of knighthood.'

$143.00 (USD) $85.80 (USD)

Sermons on the Song of Songs, II

By Gilbert of Hoyland; Translated by Lawrence C. Braceland SJ

Series: Monastic Studies Series 22

ISBN: 978-1-60724-204-8

Taking up Saint Bernard's unfinished sermon-commentary, Gilbert ruminates on verse 3:1-5:10 in forty-eight sermons, leaving the task to be finished by John of Ford.

$165.00 (USD) $99.00 (USD)

The Letters, I

Series: Monastic Studies Series 27

ISBN: 978-1-60724-205-5

These are the letters of Adam of Perseigne, Spiritual director to kings and clerics, nuns and nobles and adviser to Richard the Lion-hearted; Adam also found favor at the witty court of the Countess of Champagne.

$166.00 (USD) $99.60 (USD)

The Art of Preaching

By Alan of Lille; Translation and Introduction by Gillian R. Evans

Series: Monastic Studies Series 28

ISBN: 978-1-60724-206-2

Preaching was a much admired, much studied, and much practiced art by both abbots and secular clergy. This handbook designed for training future preachers gives moderns an insight into the technique and the content of those twelfth-century sermons.

$158.00 (USD) $94.80 (USD)

Sermons on Conversion

By Bernard of Clairvaux; Translation and Introduction by Marie-Bernard Saïd

Series: Monastic Studies Series 29

ISBN: 978-1-60724-207-9

The burgundian reformer abbot draws a picture of the perfect frontier bishop, and holds him up as a model for bishops everywhere. Conversion is used here not in the modern sense of transferring from one ecclesiastical body to another, but in the patristic and monastic sense of metanoia, turning one's entire being wholly to God.

$178.00 (USD) $106.80 (USD)

Commentary on the Seven Catholic Epistles

Series: Monastic Studies Series 30

ISBN: 978-1-60724-208-6

Best known in the Middle Ages as a scriptural exegete, Bede here provides a running gloss on the Letters of James, Peter, John, and Jude. Why he chose these `lesser letters' for his first attempt at written exegesis no one knows; perhaps he did so because so few other scriptural commentators had glossed them. They are unique in that he inclined more to the literal interpretation of the text than he did in his more allegorical later commentaries. Preachers will find them useful; readers will find them illuminating.

$177.00 (USD) $106.20 (USD)

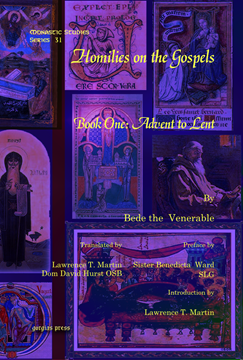

Homilies on the Gospels

Book One: Advent to Lent

By Bede the Venerable; Translated by Lawrence T. Martin & Dom David Hurst OSB; Preface by Sister Benedicta Ward SLG; Introduction by Lawrence T. Martin

Series: Monastic Studies Series 31

ISBN: 978-1-60724-209-3

From the eighth to the fifteenth centuries, Bede's authority as a scriptural exegete was second only to that of the Doctors of the Latin Church. Yet modern readers associate this remarkable scholar-monk only with his History of the English Church and Nation and ignore the works he saw as his chief accomplishment.

$154.00 (USD) $92.40 (USD)